Religion, Fashion, and Belief

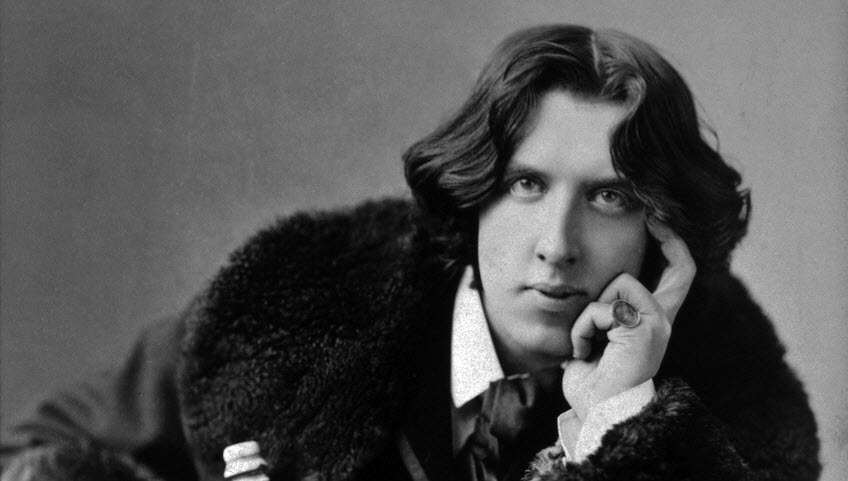

In this note, we will use the principles of Discovering the Soul of Your Story to identify potential story issues in an aphorism about religion, fashion, and belief and create a story sketch from one of the issues. Specifically, we will look at an aphorism attributed to 19th-century poet, novelist, and playwright Oscar Wilde:

"Religion is the fashionable substitute for belief."

This aphorism references the important distinction between genuine belief and the mere appearance of belief, and it levels the broadly stated charge that religion serves as a socially acceptable means of pretending to a belief that one might not have. The story issues that it spawns are likely to address matters related to religion, faith, fashion, honesty, belief systems, social inclusion, and truth and might include (to name a few):

- Pretending to embrace a system of thought in order to attain or retain social status

- Defying conventional belief systems

- Deluding oneself in order to function in society

- Seeking unconventional truth

- Challenging accepted belief systems

- Attempting to maintain one's sense of self in the face of social pressure to conform

Any of these issues might serve as the starting point for the creation of a satisfying story. For example, the issue:

- Deluding oneself in order to function in society

is expressed in the attitude of the townspeople in the Hans Christian Andersen tale, The Emperor's New Clothes, where none of the adults wants to risk admitting the obvious fact that the emperor is not wearing any clothes. And if a story were written with one of the townspeople as its main character, it might rely on this issue to drive its thematic engine—specifically, the fear on the part of the main character of being ostracized for not embracing the accepted norm of belief.

The issue of deluding oneself in order to function in society drives both The Emperor's New Clothes and 1984.

That same issue lies at the heart of the George Orwell novel 1984, where the main character, Winston Smith, must struggle with his true feelings regarding the totalitarian society in which he lives—which is ruled by a government that demands not just obedience from its citizens but complete acceptance of its tenets, however ludicrous they might be.

Likewise, the issue:

- Seeking unconventional truth

is expressed by the main character in the film Altered States, scientist Eddie Jessup, who attempts to explore (gain knowledge of) altered states of consciousness. And the issue:

- Attempting to maintain one's sense of self in the face of social pressure to conform

manifests as an important part of the film The Magdalene Sisters, where three girls sentenced to life in a 1960s Irish sisterhood asylum attempt to keep their senses of self in the face of pressure to accept and conform to a system that pretends to righteousness.

Any issue extracted in this manner from the aphorism given above can be used as the starting point for creating a story. And Part Three of Discovering the Soul of Your Story describes the steps for doing so—a process that involves: inventing a main character and developing her course of action and endeavor, creating the proposition, and building the story from there.

Brief Example—A Story of Defiance

As an example of the process described above, let's put together a quick sketch of a story derived from the issue of "defying conventional belief systems." And let's set the story in the world of science, where objectivity is sometimes trumped by emotional investment in longstanding theories, leading to a lumbering inertia with regard to new ideas. (For real-world examples, one need look no further than the travails of Ludwig Boltzmann, who developed statistical mechanics, or the difficulties that Edward Witten is reported to have had in gaining acceptance of M Theory.)

Let's put together a story derived from the issue of "defying conventional belief systems."

And let's imagine that our main character is a theoretical physicist who has discovered a groundbreaking new way of modeling the fundamental forces in the universe—not quite a Theory of Everything, but a major step in that direction. And let's further assume that her discovery is supported quite strongly by the evidence and looks to be entirely valid.

To create the sketch of the story, we must first translate the issue into a course of action

To create the sketch of the story, we must first translate the issue into a course of action on the part of our main character, which in this case would simply involve her attempt to gain acceptance of her theory by the scientific community in the large. And to translate the course of action into an endeavor that the audience can judge as worthy or not, we must assign a how and why to her attempt. So, for the sake of simplicity, let's make her actions "by the academic book" and her motivations noble, stemming from a genuine desire to advance scientific knowledge rather than simply to make a name for herself.

So our main character is an intelligent and moral heroine whom the audience can root for to succeed. And the proposition of the story is likely to support the idea that her endeavor is advisable. (For a formal method of stating story propositions, see "Short Tour—Meta-adaptation.")

Our heroine will be challenged and opposed both personally and intellectually at every turn.

It is important to note here that our heroine's journey in the story does not merely involve her attempt to publicize her new idea. It involves doing so against the backdrop of a community whose denizens are likely to be heavily invested in the conventional ideas that are threatened by that idea and upon which many have based their careers. Consequently, she will be challenged at every turn and opposed personally as well as intellectually. But is also likely to be aided by personal and professional allies along the way.

The opposition may wear her down to the point of breaking.

The opposition may serve a grand purpose of forcing her to refine and develop the mathematics to defend her theory, but it may also wear her down to the point of breaking—as it appears to have done to Boltzmann, who committed suicide by hanging himself in 1906. And the audience will ride along on her journey to learn whether she succeeds or fails in the face of that opposition.

So here we have the rough sketch of a story about a physicist attempting to gain acceptance of a new scientific theory, and the story idea derives from an aphorism about fashionable belief.

Is the connection between these ideas tenuous? Perhaps. Does it matter? Not at all. The concepts presented in Discovering the Soul of Your Story are not about formulaic storytelling; they're about (in this case) establishing lines of questioning that can lead to purposeful riffing.

And for a writer, riffing is no crime.

For More Information

For details regarding the concepts and terms mentioned in this article, please refer to the resource materials.

Members-only Content

This article is available only to logged-in members of this website.

If you're already a member, go here to log in.

Not a member? Not a problem. Join for free!

0 Comments