Guarded Praise for a Global Language

As I was walking in downtown Chicago a few years ago with a friend and fellow writer, it suddenly struck me to ask her if she'd ever heard of Esperanto. The question did not burst out of the blue, of course (I'm not demonstrably psychotic and don't hear voices on weeknights), but I honestly cannot recall what sort of conversational Brownian motion brought us to point where the subject was in any way relevant. It's likely that we'd been discussing language in general, as writers are wont to do. In any case, the answer was "no," she had never heard of Esperanto. Which allowed me to wallow briefly in that strange delight one feels when one finds a virgin audience for an obscure subject that one knows at least a little bit about. I don't hang my life on such moments, but neither do I allow them to escape un-wrangled.

A universal language we might use to understand each other more clearly... now wouldn't that be something.

I first heard of Esperanto in the mid-1960s—a time of grammar school innocence for me, when the world seemed large, James Bond plots seemed less implausible, and my interest in international affairs was wet-nursed by a Saturday morning kids' show called The Big Blue Marble, sponsored by ITT. I knew nothing about Esperanto at the time except for its name, but the very idea of it fascinated me—a universal language we might use to understand each other more clearly... now wouldn't that be something. In the polyglot world of that era, differences in languages seemed like unnecessary and artificial barriers to me.

For some reason, I assumed that it was a modern construction—something cooked up 60s-style to bring the world together for the Age of Aquarius. Only when the remembrance of it came to me a few years prior to the stroll with my friend did I do a little research and discover the truth… that it preceded the Summer of Love by roughly 80 years.

What makes Esperanto attractive is its simplicity. One can easily and confidently pronounce any Esperanto word upon first encounter.

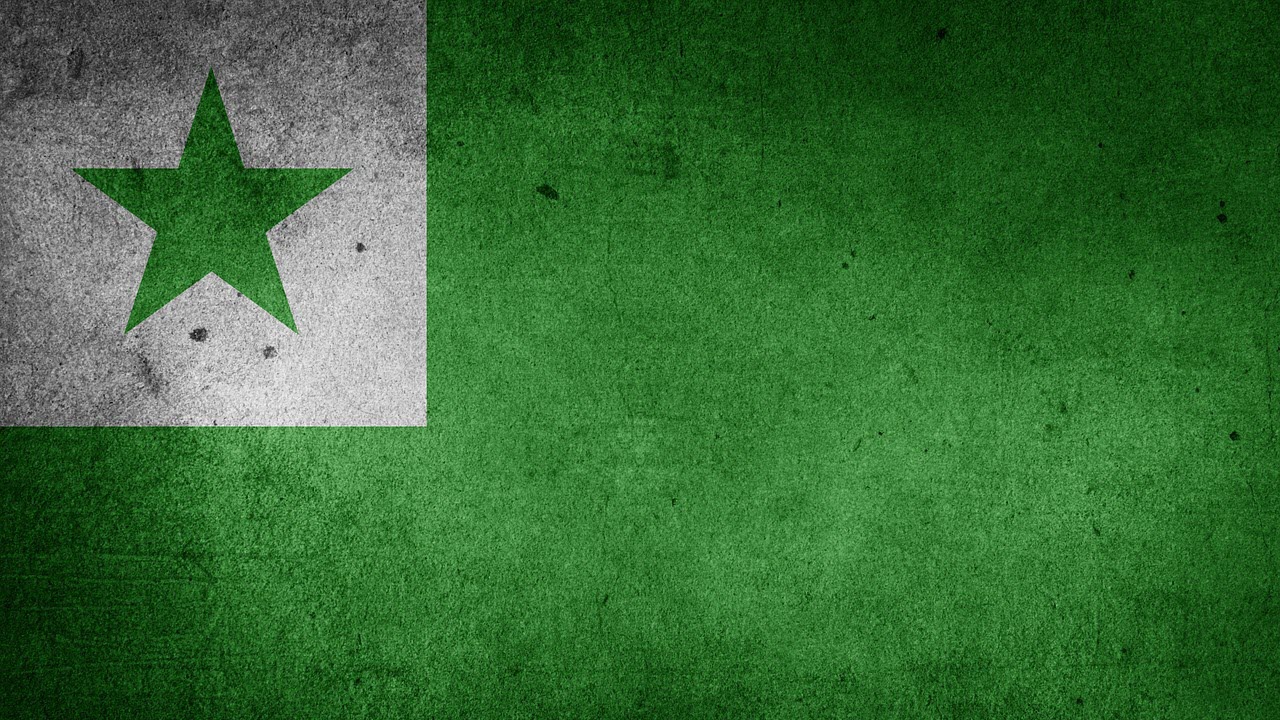

Esperanto was invented in 1887 by Dr. Ludvic Lazarus Zamenhof, a Polish ophthalmologist and philologist whose upbringing exposed him to many different languages—including Russian, German, Polish, and Yiddish—and who later studied French, Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and English. He never meant for Esperanto to replace the world's many languages. Rather, he hoped it would serve as a second, common language that would allow people of all nationalities to communicate clearly with each other while retaining the cultural identities of their respective homeland tongues.

What makes Esperanto attractive is its simplicity. The Esperanto alphabet, for example, contains 28 letters, but each letter corresponds to only one sound, and each sound corresponds to only one letter. Consequently, one doesn't encounter the goofy quirks of English, where, for example, the letter combination "gh" can be pronounced either as a hard "g" (ghost), an "f" (laugh), or not at all (night). As a result, one can easily and confidently pronounce any Esperanto word upon first encounter.

With regard to grammar, Esperanto really shines, because it is built on only 16 grammatical rules.

Pronouncing words is only a first step in speaking a language, of course; there's that whole nasty business of grammar. And that's where Esperanto really shines, because it is built on only 16 grammatical rules. All singular nouns, for example, end in "o"—all plural nouns end in "oj" (pronounced "oy"). All adjectives and adverbs end in "a" and "e," respectively. Nouns are not subject to grammatical gender, the one definite article is "la," there is no indefinite article, verbs undergo no change with regard to person or number... and so on.

Congratulations. You have just read a substantial portion of the entire set of grammatical rules for Esperanto.

It must be noted that Esperanto has undergone slight modifications over the years and that it is not the only constructed language in the world. There's Ido (a variation of Esperanto), Interlingua, Novial, Occidental, and even Klingon. But it is one of the most widely spoken of the constructed international auxiliary languages and might have as many as two million speakers worldwide.

Only two movies have ever been filmed entirely in Esperanto, including the 1966 film Incubus starring William Shatner.

In addition to television and radio stations that broadcast in Esperanto, there are Esperanto-promoting communities on the Internet and even travel exchange programs that will offer you a free place to stay in a foreign country as long as you promise to speak only Esperanto. (By the way, only two movies have ever been filmed entirely in Esperanto, one of which is a 1966 black-and-white film called Incubus, starring William Shatner, who would later find himself acting in films where other actors spoke Klingon.)

Esperanto's great strength may also be its primary weakness.

Oddly enough, Esperanto's great strength may also be its primary weakness—at least for the purposes of nuance. That is, its simplicity and ease of use render it less prone to slang and dialectical variation. It is also barren soil for the archaisms that can imbue a sentence with meaning drawn from some common human experience in the deep past. In my youth, the absence of such things would have recommended the language all the more. I wanted the world to be clean and efficient—as it never actually has been. But as I've grown older, I've come to appreciate the beauty that a language owes to its flaws. Just as the color in a ruby or sapphire is imparted by impurities in its chemical construction, the irrational quirks in a language are partly to credit for its richness.

So here I am defending flawed languages like English. So maybe I am demonstrably psychotic, after all.

Still, the idea of Esperanto appeals to me—and as long as it retains its auxiliary status on the world stage, I'm all for it. If nothing else, I like its name, which derives from the pseudonym under which Dr. Zamenhof published the first book of Esperanto in 1887: "Doktoro Esperanto."

In the language Esperanto, the word "esperanto" means "one who hopes."

0 Comments